Oral history of the Qa’em Salavati Station

A Salavati Station is a place Where People Serve Others with Tea or Food for Divine Reward

September 17th, 2016

The Salavati station of the Qa’em Mosque in Lorestan Province (Iran), is a story of people’s involvement in the war against Iraq, people who experienced fear, homelessness and love for years to maintain the ideals they had revolted for. A station for combatants who were returning from the fronts or those headed there…

Iran’s sociopolitical state in the late 1970s was very difficult. The Shah believed himself heir to the throne of Achaemenid kings, but people overthrew his regime with their bare hands. After the Revolution, Iranians decided to build their country with faith in Imam Khomeini’s leadership. Iran would come to face many conspiracies and tread through difficult times: from terror and insecurity at its borders to people slaughtered and killed in its cities. War and the economic recession added to their misery. The confusion and disorder in deprived cities and states, particularly the ones at the western and southwestern borders which were struggling with war, was more serious.

The ’80s were full of bittersweet memories for Iran and Lorestan Province. Bitter memories of political crises and the economic sanctions imposed on the country by foreign enemies, and sweet memories of people and officials both participating in overcoming barriers. One of the sweet memories of the time is to be found at the Qa’em Mosque’s Salavati station, and it tells the tale of what people did to help defend their country.

The Qazi-Abad Neighborhood and Qa’em Mosque

Ayatollah Mahdi Qazi returned to his homeland, Khorram-Abad after he was appointed head of its Seminary in 1964. Following the city’s population growth and geographical expansion in the early 1960s, the Qazi family decided to sell part of their estates. After they sold these lands and people settled in their newly-built houses, the area was named after the Qazis “Qazi-Abad”.

Es’haq Ayyazi: “I think we were one of the first families to move to Qazi-Abad. The year was 65 or 66. Sheikh Qazi had built about 20 houses to sell and since I was working at the Alavi school, I rented one of them.”

Within a few years, Qazi-Abad became one of the best neighborhoods, due to the efforts of Ayatollah Qazi. The design of the new neighborhood’s houses was not very different from the large houses that had yards in the old city. The neighborhood’s residents were also generally from Khorram-Abad or its suburbs, and all the neighborhood needed was a mosque.

Es’haq Ayyazi: “The construction of the mosque began before 1979. Mr. Hossein Eslamdoost bought the land from Ayatollah Qazi. Ali Goodarzi, who then worked for the police but was a true revolutionary, was assigned as supervisor to manage its construction. It was finally completed in ’80 or ’81. As soon as the mosque was carpeted we began to hold daily prayers there.”

The Salavati Station

Iraq’s imposed war on Iran began in September 1980 and was a chance for the Qa’em Mosque and its neighbors to leave behind a historical and honorable memory by working to help in the war effort.

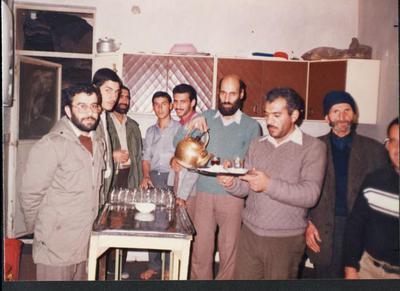

Kheirollah Memari: “When the war began, sometimes soldiers who were sent to war or were returning, passed the Qa’em Mosque on their way. The mosque was next to the same road that went to Ahvaz, where most forces were headed, and the soldiers would come to the mosque to say their prayers. We first began to serve them something simple such as tea or water. When they arrived at nights, we served them tea after their prayers. Some soldiers also brought their own food and ate it. We had been doing this for a while when Ayatollah Mianji, God bless him, brought up the idea of setting up a Salavati station in Khorram-Abad, after meeting with the Imam of the Friday Prayer, as well as the Governor and city officials. During the meeting he said that Khorram-Abad lies in the middle of the Tehran-Ahvaz and Esfahan- Ahvaz roads, and soldiers needed a rest stop along the way (the mosque). Ayatollah Mianji was aware of our activities at the mosque, so he named us at the meeting and said that we were already serving the soldiers and that if they could increase our support, then there would be no need to build a new stop. Everyone in the meeting agreed. After a while we were invited to attend one of their meetings and report our activities. They promised to support us financially and we were asked to expand our activities a bit more. So we prepared food for soldiers and started to work around the clock. The mosque had to be open at all times, and we managed to achieve this with God’s help.”

Alireza Masoudinejad: “We had begun our activities in serving the soldiers even before the station was established. Because the Qa’em Mosque was on the main highway from Tehran to Khuzestan, soldiers had to stop on the way to say their prayers and rest. At first we served them with water, tea or beverages until the station was set up.”

Abdollah Memari: “As far as I remember, in the beginning soldiers only came to the Qa’em Mosque to say their prayers and we prepared tea for them. One of our friends, Mohammad Mayeli, (who lives in Mashhad now), was very passionate about serving these soldiers, and despite working for the Gendarmerie, he used to come to the mosque for this very reason. A while later, we thought it would be better to prepare food in addition to tea … and this is how the Qa’em Mosque became a Salavati Station.”

When the station was set up, Kheirollah Memari was appointed manager. He assigned an active staff for the station and put them to work in different work shifts. Each staff member was supposed to work 12 hours a week. But some of them went there every day because they lived so close to the mosque.

Mohammad Mayeli: “We went to the mosque every day. I used to work in the Gendarmerie, and as soon as I left work, I went home, had a quick lunch and then went to the mosque. I would stay there until 11 or 12 at night or as long as it took to finish the chores such as washing the dishes, and preparing food…I really enjoyed what I did.”

The staff’s active members were mostly merchants and shopkeepers from the neighborhood. Normally in every work shift 5 or 6 staff members were present. There was systematic discipline at the station. Mr. Memari defined everyone’s responsibilities and registered the exact numbers of guests arriving at the station in his note book.”

Kheirollah Memari: “I used to take note of the number of people who entered and left our mosque. I would ask a group’s accompanying supervisor: ‘Where are you from? How many are in your group?’ They used to come from Isfahan, Zanjan, Hamedan or Tehran. I used to write the information down and save it in a notebook.”

The way Mr. Memari managed the station was the key to the station’s stability and persistence. His lifestyle during those years is also noteworthy.

Alireza Masoudinejad: “Mr. Memari was a funny person. He always joked aroung with every one and created a fun and intimate atmosphere wherever he was. It was his style. He didn’t want the staff to work in a bad mood. Once I had to assist him for a few days, so I accompanied him wherever he went from morning to night. He used to leave home at dawn, went straight to the mosque and checked everything. He took note of what was needed to later ask Mr. Taghavi, our station’s driver, to buy them. He then arrived to his office at the “Imam Khomeini Relief Foundation” before 7 o’clock, as he was the head of the foundation’s branch in Khorram-Abad, and a member of the foundation’s council in the province. In his office, he registered and organized letters, controlled plans and staff attendance carefully until 9 or 10 o’clock and he did it all without asking for payment. Then he’d lock his door and hand everything over to his assistant and deputy. After that, he would go to his shop in Vesal St. and change into his uniform: Mr. Memari was a glazier and he glazed car windows. His two brothers and some workers also worked there, and he worked until noon. Their hands were dirtied with grease, oil, and adhesives so they used to wash it with some warm water they’d keep on top of an oil heater. He’d then do ablution to prepare to go for noon prayers at the mosque. He’d supervise everything and then go home for lunch. In the afternoon he’d go back to the foundation and stay there until 3:30 or 4. Then he’d go back to his shop and work until evening, and again go to mosque to say his prayers and after that if there was a meeting or something scheduled, he’d see to it. This was how he spent his days for a long time.”

Moving out of the city

Iraq’s air raids on residential areas during the 8-year war was one of Saddam’s many inhumane acts against Iranians. Khorram-Abad suffered a lot from these air raids. This city alone was attacked more than 140 times during the war, and the air raids resulted in the deaths of more than 2300 civilians. The threat of air raids on the Qa’em Mosque forced the management of the station to change its location and move to Palestine St. at first, and then to the Taleqan Neighborhood.

Mohammad Mayeli: “Palestine St. was in the Jewish part of the city, but they all but one had deserted the place right after the Revolution and went to occupied Palestine. All the properties were left to one of them who later converted to Islam, Mr. Javaheri. Khorram-Abad’s Seminary divided these lands among the deprived and the farmers. They also paved the roads and people built their houses on the lands. They also built a new mosque and named it “al-Aqsa”, and we transferred our station to this mosque.”

Kheirollah Memari: “We moved to Palestine St. when the bombing started. Some of our staff had already left to the suburbs with their families and the number of our staff was reduced.”

The Al-Aqsa mosque was located far from the main highway. A guide stationed on the way helped soldiers and passengers to the new location. This job was left to members of the mobilization forces (Basij) of the Qa’em Mosque.

Qasem Ali Abdi: “We sent our Basij members to the city entrance to guide people. We did this for a few months. But when Iraq started to attack Khorram-Abad we moved to Taleqan.”

Qasem Seif: “One day I was at the station at the mosque on Palestine St. and was washing beans to cook them for dinner. Around 11:30, I put the beans in the pot, added some onions and let it simmer, then I went home. When I arrived home, someone said the mosque on Palestine St. had been attacked. The planes had hit a place adjacent to the mosque but the damage was serious. We decided to close down our station there and move to Taleqan.”

Abbas Alishahi: “In late 86, Khorram-Abad was attacked every other day. Some places near the station were hit a few times, so the station’s staff suggested it be transferred somewhere else. We took the matter up with officials and it was approved. The station was then moved to the mosque in Taleqan and we continued on. Later when the station was moved back to the Qa’em Mosque, villagers in Taleqan continued to welcome soldiers in their mosque.”

Even during the air raids, the Salavati stations were continuously operated by the people of Khorram-Abad, whether the station was in the Qa’em Mosque, Palestine St. or Taleqan.

Eshagh Ayyazi: “We (men) were in charge of preparing food and serving. The women made pickles and knitted clothes for soldiers. Some of us even washed the bodies of the dead after the air raids […] At certain times had we not taken it upon us to do so, there would have been no one to retrieve and wash the corpses…”

Women’s Role

The work done by women at the station was impressive. They started to work early in the morning, dusted the mosque, cooked lunch for guests and then at noon they handed over their responsibilities to the men.

Mrs. Mohammadipour: “We washed carrots, potatoes, eggplants, … if a blanket was dirty or had a blood stain on it and we were told to wash it, we washed it with our feet. We washed the dishes, dusted the mosque and swept everywhere.”

Kheirollah Memari: “Some women joined and helped us. They used to come before sunrise, cleaned the mosque, yard, toilets and swept and mopped everywhere. They used to work in two shifts, and my wife was their supervisor. They washed pots and dishes leftover from the previous night’s dinner, cooked lunch and dinner, and left at about 11.”

The Station’s Security

MEK agents (Mujahedin-e-Khalq) were responsible for a lot of terrorist attacks against citizens in the 1980s. Their penetration in different cities made Basij members vigilant to protect the station and its neighborhood. Basij members were the best choice for the job since they knew the locals and the neighborhood better than anyone else.

Kheirollah Memari: ” There was an office at the corner of the yard that belonged to the Basij. They were in charge of securing the mosque and its surroundings. At nights when cars, buses or trucks sending cargo to the front arrived and stopped outside of the mosque, we told them not to worry since our Basij would guard them. They were always vigilant despite their being tired, and their cooperation helped us perform our job perfectly. The Basij who guarded outside were the same ones who worked at the station. They weren’t brought in from outside.”

Abdollah Memari: “We had a base at the mosque even before the Salavati Station was established: the Shahid Mobasher base. I used to guard the mosque on Mondays. We were always guarding the place, especially after the station was set up.”

Operation Mersad

The war had just ended when the MEK attacked Iran with the help of Iraq’s Baath Regime. The station hadn’t completely closed down yet when we had to open it again.

Kheirollah Memari: “When resolution 597 was approved, we all felt something was missing. It was like getting fired from your job […] It was around then that Operation Mersad happened. Our staff were leaving their positions when we were suddenly called back, and a lot of soldiers went to fight. We prepared a lot and didn’t rest for three days. The soldiers who passed our station at the time were mostly from Tehran, Zanjan, Hamedan, Qom and Isfahan […] Once we even had to serve 1000 people in one day.”

The Imam’s Departure

During the last years of the war, there came a chance for the station’s staff to visit Imam Khomeini. They considered it the best reward they could ask for. Less than a year after their visit, Imam Khomeini passed away, so the station’s staff decided to do something meaningful. That’s why on the Imam’s first anniversary, they set up their station to serve the caravans going to visit Imam’s shrine.

Kheirollah Memari: “We all gathered and decided to visit Ayatollah Mianji […] once a week. […] We had asked him to set a date for us to visit Imam Khomeini as a reward for our staff and he promised he would see to it. But Ayatollah Taheri Esfahani, who was the Friday Prayer Imam of Isfahan, helped us accomplish that sooner. He had once come to visit our station, and the women were also there, so when Ayatollah Esfahani entered with three or four guards, they started to pray for him loudly, and he greeted them. One of the ladies told him they really wanted to visit Imam Khomeini and since he had the authority, she asked him to do something about it, and he said he’d try to arrange it. After a short while, we were called and were told that we can visit the Imam with 100 people from our staff on a certain day. We arranged transportation and went there. The visit was truly sublime. Everyone was touched by the Imam’s presence but unfortunately he was sick and couldn’t speak for a longer time. They named our group among other visitors as the staff of the Qa’em Mosque’s Salavati Station in Lorestan.”

Mohammad Mayeli: “When the Imam was still alive, we went to visit him with one or two buses full of people. He was sitting on a balcony and we were sitting down on the lower floor. He delivered a speech and we later returned. After the Imam’s passed away, at the anniversary of his departure, we went on the road that led to the Imam’s shrine next to the police station and set up our station with the help of our staff: Mr. Memari, Jamaati, Sedaghati, Shishei and Gooshei. There was a place where everyone parked their cars and continued their journey on foot, and that’s where we set up out tents. We filled our pots with a large water container we had brought from Khorram-Abad and served tea or boiled water. We did this for a day and a night. In the afternoon, we collected our stuff, went to Qom to rest and returned to Khorram-Abad.