Alireza Khaleqi: Revolutionary art and memory

What Is Particularly Striking about Khaleqi's Art Is the Connection between the Purpose, the Art, and the People.

November 13th, 2016

The dissemination of revolution to the masses is a crucial aspect demarcating fruition or failure. Imagery and rhetoric can flourish independently, however their intertwining and relevance to the moment provide the metaphorical form of ideological unity against the perceived and experienced oppression of the state. Iranian artist Alireza Khaleqi is an example of how art can mobilize the people, while leaving a tangible memory of the shaping of history.

Khaleqi’s talent was noticed in his early years of schooling by teachers who encouraged his pursuits. In his teenage years, both art lessons taken in high school and his father’s opening of a calligraphy studio provided Khaleqi with the opportunity to perfect and amalgamate both artistic expressions, which would come in useful during the period of resistance when public spaces became the primary means through which revolutionary ideology would be disseminated.

As the mosques became spaces for initial dissent, Khaleqi’s artwork became politically motivated by 1973, with the first painting being an expression of people’s deprivation of freedom under the Shah Reza Pahlavi. The first direct rebellion on Khaleqi’s part against the Shah’s rule happened during a high school art competition, when he switched from the black pencil category to oils, in order to refuse drawing a portrait of the Shah.

In a brief conversation with Khaleqi, a sense of cultural and revolutionary consciousness emerges that relates directly to his role in the Islamic revolution. Khaleqi distinguishes between two important phases with precision – namely the revolutionary process and the importance of collective memory. Both are expressed in his art, thus rendering the artist an important component of this particular phase of Iranian history.

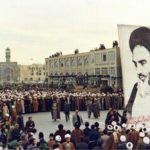

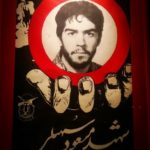

Expanding further on the role of the artist in history and his commitment towards the revolution, Khaleqi stated, “A revolutionary artist always has the revolution’s goals in mind, and the successful application of this revolutionary art has its own time and place.” Indeed, Khaleqi’s consciousness is perhaps one of the most striking elements portrayed in his art; there is a sense of urgency, perhaps best perceived through the different roles that he immersed himself into. Apart from art and calligraphy, which were the main mediums through which the revolutionary message was imparted to the people, he also filmed demonstrations which, perhaps, also influenced the dedication with which portraits of the martyrs became a prominent feature of Khaleqi’s work.

Khaleqi’s art weaves a narration that spans various concepts of evolution. There is the evolution of the artist himself, which occurs within the span of resistance against the Shah, the implementation of the Islamic Revolution and the maintaining of the revolution. In Khaleqi’s own words, “A revolutionary artist works to achieve the revolution’s goals by accomplishing his duties, and he is under greater obligation than others to do so.” This constant awareness is further illustrated by the artist as maintaining “a cultural resistance”, which he speaks about mainly in relation to international attempts to isolate Iran.

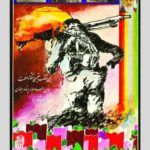

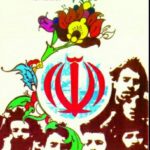

Indeed when it comes to the dynamics of isolation, Iran has managed to maintain a consistent stance when it comes to combating the isolation of Palestine by the international community. One of Khaleqi’s posters in watercolor and gouache depicts solidarity with Palestine on International Quds Day. This is not only a reflection of Iranian support for Palestine but also the artist’s awareness of Palestinian anti-colonial struggle which dates back prior to the Islamic Revolution. Reflecting on Palestine as a tangible source of inspiration, Khaleqi remarked: “Recalling my teenage years, from the days before the Islamic Revolution, I believe that the people of Palestine were always considered a symbol of resistance.”

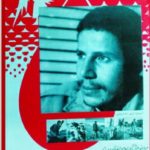

Although the issue of cultural awareness is given a present concept, it is clear that Khaleqi worked within such awareness to produce his art. It is also possible to apply the same initiatives that sustained the revolution to the process necessary to maintain its extension by analyzing Khaleqi’s work as an expression of historical and collective memory. Besides the colors dominating much of the posters and calligraphy in black and red, which implied both urgency in imparting the message as well as the more practical concerns of completing slogans on walls in a brief time to avoid detection and capture, the subjects themselves testify to Khaleqi’s manner of capturing both the necessity and the human aspect of the Islamic Revolution and its participants. The artist exposes his evolution as an individual participant in the revolution and also as part of the collective, rather than a spectator.

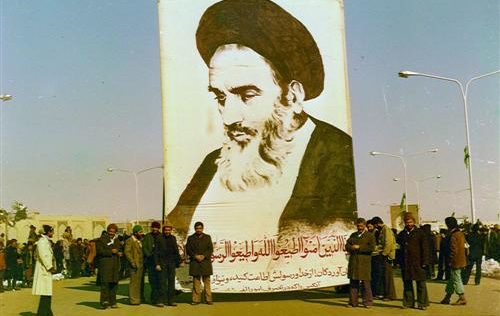

While the large oil paintings of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini go a long way in capturing what is considered the epitome of the Islamic Revolution, a considerable effort has been exerted in remembering Iranian anti-imperialist figures as well as the martyrs of the revolution. Khaleqi’s art spans a timeframe that extends into Iran’s past, yet links to the Islamic Revolution through historical details. An example of such sequences would be the poster of Seyyed Hassan Modarres – an Iranian cleric who fought British forces in Persia and who was also one of Khomeini’s teachers. Ayatollah Morteza Motahhari, a philosopher, lecturer and politician who was assassinated in May 1979, is another of Khaleqi’s subjects commemorated through his art.

A striking painting by Khaleqi depicts Mohammed Ebrahim Hemmat, who at an early age was involved in resistance against the Shah’s regime, leading to his being persecuted by the SAVAK and wanted dead, thus prompting him to continue his activities in secret. Killed during Operation Kheibar in the Iran-Iraq war, Khaleqi’s painting depicts a pensive Hemmat against a dark, turbulent background, with the pale silhouettes of three soldiers seemingly emanated from memory.

What is particularly striking about Khaleqi’s art is the connection between the purpose, the art, and the people. While the depictions themselves carry a strong narration of the Iranian Revolution’s particular history, it is also through the amalgamation of art and remembrance that Khaleqi’s talent becomes an expression of the collective supporting the revolution. It is an individual affirmation that performs its extension not through appropriation. It relies upon participation, on the artist’s behalf particularly through his active involvement, as opposed to being a passive spectator.