Memoirs of the Qa’em Mosque’s Salavati Station

Memories of Iranians’ Love for their Country, Memories of what Happened at the Station

September 17th, 2016

The staff who worked at the Salavati station at the Qa’em mosque have a lot of memories of their eight-year long activities. We share a few of these memories in the following notes.

A Sheep With Four Horns

Kheirollah Memari: “Some people from Khurasgan in Isfahan would sometimes pass by the station, and whenever they went to the front, they brought gifts and donations for the soldiers, things such as goats or sheep. They collected donations and sent them to war zones. Sometimes they sent 10 or 15 trucks, each loaded with about 20 goats or sheep. They arrived at our station at night and then left the next morning. I remember it was during the month of Ramadan and I was sitting behind my desk in the corridor, taking notes on the number of groups and soldiers we had served that day. Suddenly a boy who didn’t look more than eight or nine, and had sunburned skin, approached my desk and leaned his chin on it. I said: “You should be sleeping!” He said he couldn’t sleep sleep a wink because he was so thrilled about going to visit war zones for the first time. So I found him to be an interesting young man and asked the staff to bring him tea. Then he asked me: “Do you want to see something interesting?” to which I said yes. He asked if I had ever seen a sheep with four horns. Although Lorestan was famous for sheep husbandry, I had never before seen such a thing. He brought me to one of their trucks, then jumped up to the trunk, where the animals were kept, and brought one to the front. It was a big fat sheep with four horns. He explained it was his sheep and his grandfather had given it to him when it was a lamb as a gift. He raised it until it turned into a big sheep and now he wanted to give it to the soldiers, on the condition, that his parents agree to let him join the soldiers. The boy of two or three years ago, who loved his sheep dearly, had now grown up and wanted to donate his beloved sheep…”

Shrouded

Mohammad Mayeli: “Before Quds Day, the Iraqis had announced that they would bombard wherever people came out to demonstrate in the streets. We gathered near the Qa’em Mosque and hid while wearing shrouds. We started to move from the mosque, men and women together, and joined the large demonstration in the city. Iraqi fighters came and bombarded the city but no serious damage was done. No one was afraid, as they did this out of love for God, so we were ready to die. I have a photo from that day of us wearing shrouds and holding each other’s hands.”

Abdollah Memari: “Saddam had said that they would hit Khorram-Abad on Quds Day. I remember how we prepared some shrouds, wore them and started the demonstration from the Qa’em Mosque. We passed a few streets until we joined the main demonstration.”

Sirens and Death

Mohammad Mayeli: “Our house was located on a long and wide street. The Revolutionary Guard had dug a large shelter in front of our house which we used to protect ourselves against air raids. Whenever we heard warning sirens we ran to the shelter. Once when the Iraqi jets launched an artillery barrage on houses, our house was hit with my mother-in-law inside. She had to be hospitalized for a while but thank God she was safe. This enemy had no mercy.

Mr. Shishei was a staff member in our station. His family and relatives took cover in a shelter they had made in the basement of their house when the attack happened. The artillery struck the basement and all of them were killed, about 10 or 12 people, and he was left alone. In the street, whenever we heard warning sirens, we jumped straight into the water canals. When we wanted to get up, there’d be four or five people on top of us. In the Bazaar (market), we went into the storage rooms and hid under bags filled with sands that we had prepared for such an occasion […] When the fighters arrived, they flew so close to the ground that we could see their pilots.

The city was a ghost town. Each family had to hold their funeral alone. When the city was bombarded, the mountain would become hot and red. When it happened at night, we woke up to the sound of the sirens. We were like mad men and didn’t know what to do. I remember, my wife and I used to hug the walls or corners, so that if the house collapsed, we would bear less damage. Sometimes I ran faster than my child to secure myself. (It was such a difficult situation that) every one tried to save themselves. When we went to the cemetery, the burials were held with a small number of people, while before 100 or 200 people would be there.

Abdollah Memari: “Mr. Majid Eskandari wanted to get married. We introduced him to a girl whose father, Mr. Khedmati, used to come to our mosque and help. Majid and his family went to the girl’s house. After a while I asked him what happened, so he said that they had consulted the Quran and the result wasn’t favorable. We also introduced my brother to the girl, but again when we consulted the Quran, the result was also unfavorable. The same thing happened yet again with his brother-in-law. Finally, the girl married her cousin from Borojerd and went there to live, and eventually they had a son… Mr. Khedmati was a gentle and nice man and was as a relative of Mr. Shishei, who worked at the station with his two sons Majid and Hamid.

One day the girl and her new family came to Khorram-Abad to visit their relatives. They were in Mr. Shishei’s house when the city was attacked. 11 people were killed there and the girl’s husband and her son were among the dead. We came to the conclusion that whoever was to marry that girl, was supposed to be martyred on that day. It was a very sad and tragic event. Mr. Shishei was on a trip that day and he wasn’t home. But his wife and mother were also killed.”

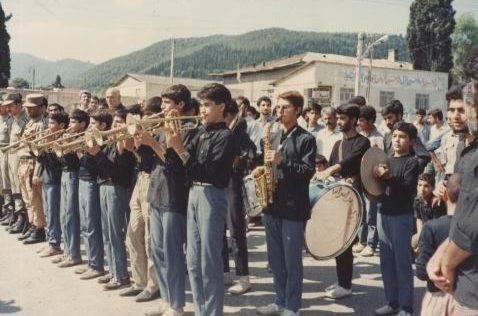

The Victorious Nation

Kheirollah Memari: “Once Seyyed Aref Hussein Husseini, the leader of the Shia community in Pakistan, came to visit Iran’s troops at the front with a Pakistani commander. They arrived at our station at night. Their guide was Mr. Zeinoddin who had lost two of his sons in the war. They came to the mosque, ate something and left afterwards. That night I wasn’t there. They returned after a few days. When Mr. Zeinoddin asked them where they wanted to have lunch, Aref Husseini suggested our station. I was there when they came. When they arrived to our station, I approached and welcomed them, and proceeded to explain the duties of our station and asked them for their opinion. That day, I sat next to them and while we were talking, a group of about two or three hundred soldiers arrived. I don’t remember whether they were going to or returning from the fronts. The soldiers began to say their prayers and when they were done, they were served with some food. The commander was fully concentrated on the soldiers and our staff. He was amazed by our readiness for the troops, and when the soldiers left, although he could hardly speak Persian, he said: “this nation, Iranians, even if enemies crush them ten times, they will stand up again and gain victory. The way they manage this war and support it, they will never be defeated.”

Zulbia (an Iranian sweet)

Kheirollah Memari: “There was a man from Isfahan called Mr. Rezaee who managed a number of Salavati stations at the fronts. We saw him a lot because he was always on the road securing products for his stations. He had a friend who was a bookseller, and who always accompanied him. On one Ramadan night I saw the bookseller alone. When I asked him about Mr. Rezaee, he said that Mr. Rezaee’s second son was martyred in the war, and that he was in Isfahan holding his son’s funeral. I asked the bookseller to offer him our condolences because we were busy and couldn’t attend the funeral.

Three days later, I was in my shop when the phone rang: It was Mr. Rezaee. I thought he had called to thank me for sending my condolences. When I asked him where he was, he said, with a sweet thick accent, that he was at the Qa’em Mosque. I asked: “What about your son?” but he told me to hurry up and come to the station. He said because Ramadan was nearly over and the soldiers hadn’t eaten Zulubia yet, he had loaded a truckload and was sending it to the front. He also gave us three or four boxes. I stood there wondering at the greatness of this man, whose second son was martyred [and was still thinking of the soldiers]. If such a thing had happened to anyone else, they would have stayed home and mourned for a long time. But he was worried about the soldiers because they hadn’t had Zulbia.